I’m about to head back to Hawaii to spend a few days working on Illusion – and maybe get a little winter sunshine, too! This time there’ll be no sailing of course – without an engine it’s too much effort to get in and out of the marina – but heading back to the boat has had me contemplating those last couple of weeks when I was sailing up to Hawaii from Nuku Hiva. Arriving back to Vancouver I was exhausted; a friend recently used the word “depleted” which is a pretty good description. The first few weeks back were a bit of a blur: it was great to see everyone at the ‘Welcome Home’ party (thanks to all who came and gave me such a warm welcome), but somewhat overwhelming to be surrounded by so much noise and activity after all that solitary time and seven months living on the boat, most of them without a whole lot of sleep! I wrote a bit about some of my experiences at sea alone, but I thought it might be interesting, especially for those who have never done long passages, to have an idea of the kinds of things that need to be done and thought about whilst under way. It’s all relevant to group sailing too, but just a little more intense when there’s just one of you…

Watch standing – Solo sailing exaggerates the challenge of keeping watch. On all my sailing adventures, someone is appointed to keep a lookout for other ships while underway, day and night. Sometimes a crew member falls asleep

while on watch, but I always expect someone is looking for ships and checking boat systems every 20 to 30 minutes. It is impressive how quickly a ship doing 22 knots can approach a sailing vessel doing 10 knots, head-on. If the air is not crisp and clear or the waves are large, it’s possible for a ship not to be sighted until 30-45 minutes before it passes (or collides with) us. The Automated Identification System (check out my earlier post about AIS) suddenly takes the fear and urgency out of approaching big ships. I decided that with my AIS receiver I could set a two-hour alarm and that might give me enough sleep time to stay coherent throughout the passage. As it was, I never slept more than 1 hour, so the alarm never went off. It took four days before I became aware that I was dreaming – at least then I knew I was probably getting a sustainable amount of sleep, more or less. A month after finishing the voyage, I could clearly still feel the effects of that passage, it took me at least two weeks to recover from the strangest form of sleep deprivation I’ve ever experienced.

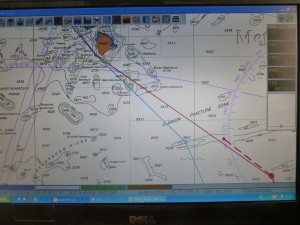

Navigation – The advent of GPS and electronic charting has made navigating the oceans much simpler and less prone to error. But it’s no less important to know that the boat is safe and on course in the middle of thousands of miles of water. I regularly checked the charts we had (NZ, US, and French) with our position and projected course to make sure that we were clear of obstructions. For example, not many people know that there are buoys out in the middle of the ocean, providing weather and ocean data for climate modelling – I had to check several and confirm clear passage on my way to Hawaii. It’s no longer just the islands that old navigators had to worry about. There’s even a submarine exercise area around Oahu! Mornings and evenings, when in the open ocean, I would check the area 24 hours (~200 nmi) ahead of Illusion. When closer to land, I’d check the course every few hours.

Navigation – The advent of GPS and electronic charting has made navigating the oceans much simpler and less prone to error. But it’s no less important to know that the boat is safe and on course in the middle of thousands of miles of water. I regularly checked the charts we had (NZ, US, and French) with our position and projected course to make sure that we were clear of obstructions. For example, not many people know that there are buoys out in the middle of the ocean, providing weather and ocean data for climate modelling – I had to check several and confirm clear passage on my way to Hawaii. It’s no longer just the islands that old navigators had to worry about. There’s even a submarine exercise area around Oahu! Mornings and evenings, when in the open ocean, I would check the area 24 hours (~200 nmi) ahead of Illusion. When closer to land, I’d check the course every few hours.

Food and meal preparation – I was bored of living off canned food: in 5 months, I’d eaten less than 10 meals off the boat! And the fresh produce I bought in Nuku Hiva would only last a few days in the tropical heat. The biggest challenge was having tins of spoilable food that were too large for one person to reasonably consume in the time before they spoiled (such as one-pound cans of tuna). I resorted to only opening tins in the evening, making a meal with half (of no more than 3-4 tins: tuna or salmon, beans, peas, spinach, mushrooms, tomatoes, olives) and enclosing the left-over tins in a big pot (away from the flies) on the gimballed stove – the only stable surface in the boat. The next day’s challenge was to make something interesting from the same ingredients as last night’s meal. Fortunately, I also had reasonably-sized tins of sardines and lots of non-refrigerated, processed cheese, so I occasionally got a break. I had no cans of fruit, so there was no fruit after the first few days when I finished the fresh stuff. I quite often had second breakfast, since I woke up for the day so early (1st breakfast about 5:30) and usually didn’t feel like eating “left-over” dinner ingredients at 10:30.

Reading and writing; listening and viewing – This was the first passage where I spent quite a lot of time reading books, finishing Melville’s Typee (an account of his visit on a whaling ship in the mid-1800’s to the very same bay in Nuku Hiva and his stay in a nearby village) and Omoo (about his sailing adventure after leaving Nuku Hiva). The books I read in Nuku Hiva and on this passage were the first non-technical books I’d been able to read on the entire journey. All my other reading was focused on understanding and rebuilding diesel injector pumps, autopilot drive arms, port check-in and check-out procedures, insurance documents, SSB-based email programs, and bluetooth module protocols. I spent most early evenings writing a personal blog to Sara. I also watched a few movies and listened to 250 podcasts! The memorable podcasts (though I understand they might not be to everybody’s taste!) were: Racaniello’s weeklies on Virology, Microbiology, and Parasitology; and Chemistry World’s weekly & little historical shorts about elements and compounds, their discovery and uses.

Sunrise, Sunset and Radio check-in – I was up for the day early enough that I could see the sun rise – that was usually the time that I moved the solar panels to point east. I would also take this time to clear the deck of flying fish that had inadvertently flown into, instead of away from, Illusion. Unlike my previous passage through the tropics, almost all of these fish were very small (and far fewer on deck) – it seems the ocean’s flying fish population is smarter than they were in 1999; evolution at work. Sunset occurred about the time of my daily radio check-in with the Pacific Seafarer’s Net, so until I was closer to Hawaii (and thus further west), I watched much of the sunset through the windows around the nav station.

Sunrise, Sunset and Radio check-in – I was up for the day early enough that I could see the sun rise – that was usually the time that I moved the solar panels to point east. I would also take this time to clear the deck of flying fish that had inadvertently flown into, instead of away from, Illusion. Unlike my previous passage through the tropics, almost all of these fish were very small (and far fewer on deck) – it seems the ocean’s flying fish population is smarter than they were in 1999; evolution at work. Sunset occurred about the time of my daily radio check-in with the Pacific Seafarer’s Net, so until I was closer to Hawaii (and thus further west), I watched much of the sunset through the windows around the nav station.

Fuel and Power – Except for the first passage out of New Zealand during which the engine got damaged, I didn’t have any engine check routines, such as checking the fuel filters, alternator belts, coolant fluid. Or checking the engine’s operating systems while running, such as temperature, charging voltage and oil pressure. I checked the state of the battery banks regularly (usually every time I passed the meter, which is centrally located) to make sure that the power consumption and voltage level made sense for the systems that were operating at the time. On my solo journey to Hawaii, I needed to make sure the solar panels were producing the most power possible, so they featured a central position in the cockpit, adjusted a few times each day to point more directly into the sun.

On my solo journey to Hawaii, I needed to make sure the solar panels were producing the most power possible, so they featured a central position in the cockpit, adjusted a few times each day to point more directly into the sun.

Sailing – Essential on a sailboat! Especially one that does not have an operational engine – and even more for the times I did not have an autopilot. The passage to Hawaii was more difficult after the first few days because the cloudy weather prevented the solar panels from fully recharging the batteries, so the autopilot could only be used for a few minutes each day. I managed to rig the sails, during the last 10 days of the passage to Hawaii, so that Illusion could sail mostly on course (usually within 30 degrees) when I slept. I also rigged a rope system from the cockpit wheel to the cabin entrance so I could easily adjust course from inside when necessary, just by pulling the rope ends. Kind of like controlling a horse, but sitting backwards in the saddle. I spent many hours steering that way!

only be used for a few minutes each day. I managed to rig the sails, during the last 10 days of the passage to Hawaii, so that Illusion could sail mostly on course (usually within 30 degrees) when I slept. I also rigged a rope system from the cockpit wheel to the cabin entrance so I could easily adjust course from inside when necessary, just by pulling the rope ends. Kind of like controlling a horse, but sitting backwards in the saddle. I spent many hours steering that way!

Hopefully that’s given you a bit of an idea of what my style of solo sailing involves! Not quite the relaxing, sun-bathing, beer-drinking experience that is often associated with boating. In fact, while under way, I didn’t drink any alcohol at all (except the obligatory salute to Neptune while crossing the equator). Being clear-headed is kind of important when your life and your boat depend on it. Anything else you’re curious about? Let me know in the comments section….